TravelVince News #46

Planos futuros e paranoias | future plans and paranoia

For English, please scroll down to 🇬🇧

Elaborei um plano para o futuro. Para tentar não perder a agilidade mental, em vez de resolver palavras-cruzadas e sudoku, me joguei no mandarim. Pode ser que jamais consiga fluência para ver um filme ou mesmo ler uma revista chinesa. O que importa é a jornada. Se ela servir para ocupar meus neurônios com caracteres, tons e todo o mistério deste idioma milenar, já terá valido a pena.

🤷🏻♂️ paranoia #1 li em uma revista médica que trabalhar à noite ou em turnos alternados aumenta o risco de demências. Lembrei dos dois anos que fui Night Manager em Londres e dos três de comissário da Emirates em Dubai e não há mirtilo com creatina para tapar o buraco. Dá-lhe mandarim!

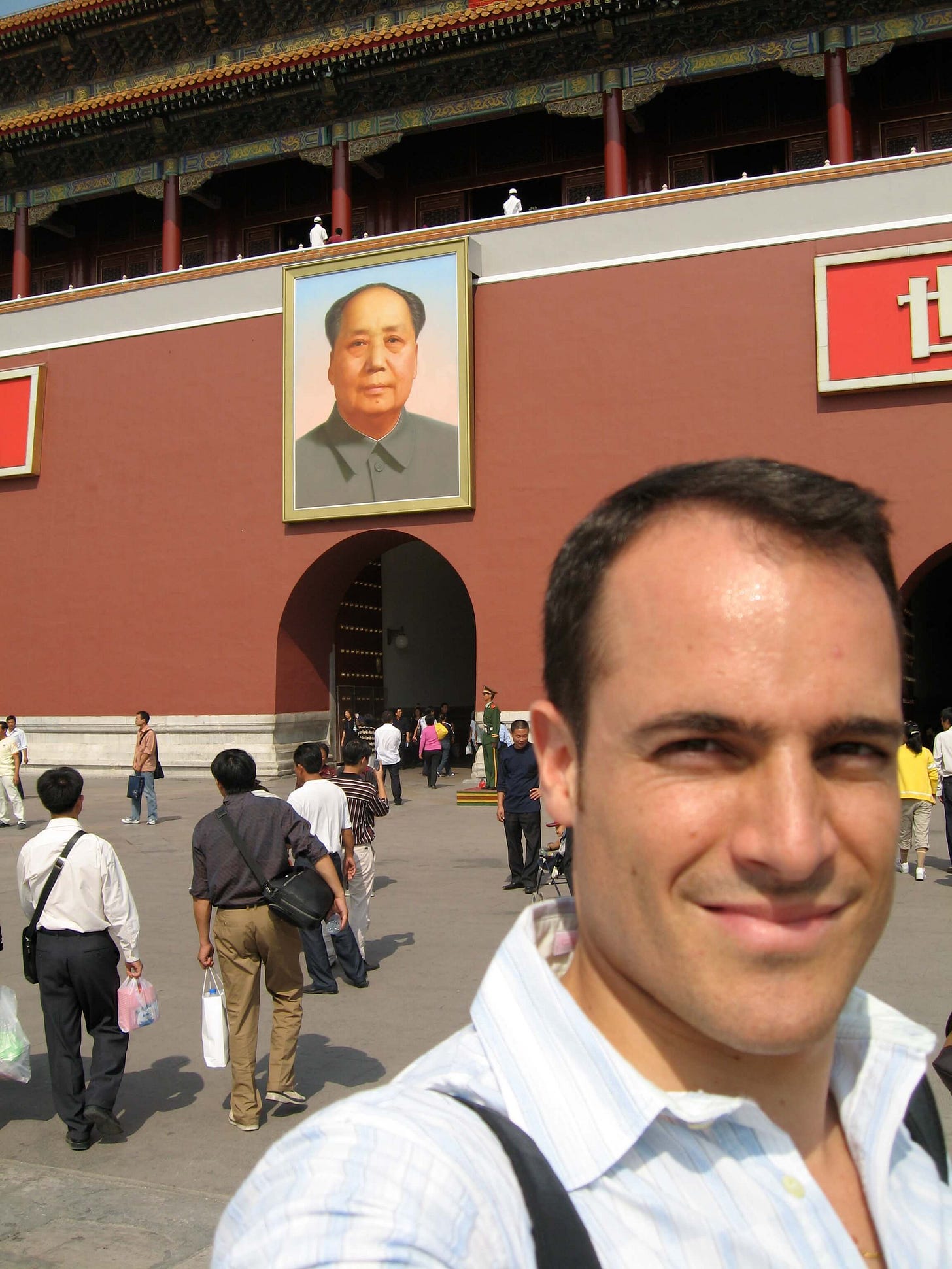

Falar mandarim não é um plano novo. Há seis anos, estava neste mesmo lugar. Tinha até mesmo uma matrícula para cursar dois meses em uma escola de idiomas em Pequim. Queria ficar semi-fluente para depois ser guia de turistas chineses em Paris. Fui para São Paulo solicitar o visto no Consulado da China, no fim de março de 2020. Éramos poucos. Os chineses que legalizavam documentos para não terem que voltar para a China me olhavam com curiosidade. Wuhan já estava bloqueada.

Só desisti quando a passagem aérea foi cancelada. A única opção seria comprar outra via Etiópia e ter que ficar 14 dias de quarentena num bunker do aeroporto de Pequim antes de poder circular pela cidade com códigos QR, máscaras, cotonetes no nariz (e até no fiofó) e medo. Mal sabia eu, naquele março de 2020, que em breve estaríamos todos vivendo algo parecido, lavando as mãos a cada hora e paranoicos com tudo.

A pandemia passou. Vieram novos problemas, que já entraram na rotina. O mundo ficou de cabeça para baixo, e a vontade de aprender mandarim continua bem acesa. Por ser tão difícil, quase impossível, me atiça ainda mais, é claro. Resolvi encarar como remédio antidemência para não perder a motivação. Prometi a mim mesmo que, se seguir as aulas online à risca e passar no primeiro teste oficial depois do Carnaval (estilo the book is on the table) compro uma passagem e me mando para a China. Poderia incorporar a artista-performer Marina Abramovic e caminhar ao logo da Grande Muralha. Ou ser um Marco Polo do século XXI.

🤷🏻♂️ paranoia #2 fico achando que se repetir os passos de 2020 tudo pode acontecer novamente, pandemia, lockdown e tudo.

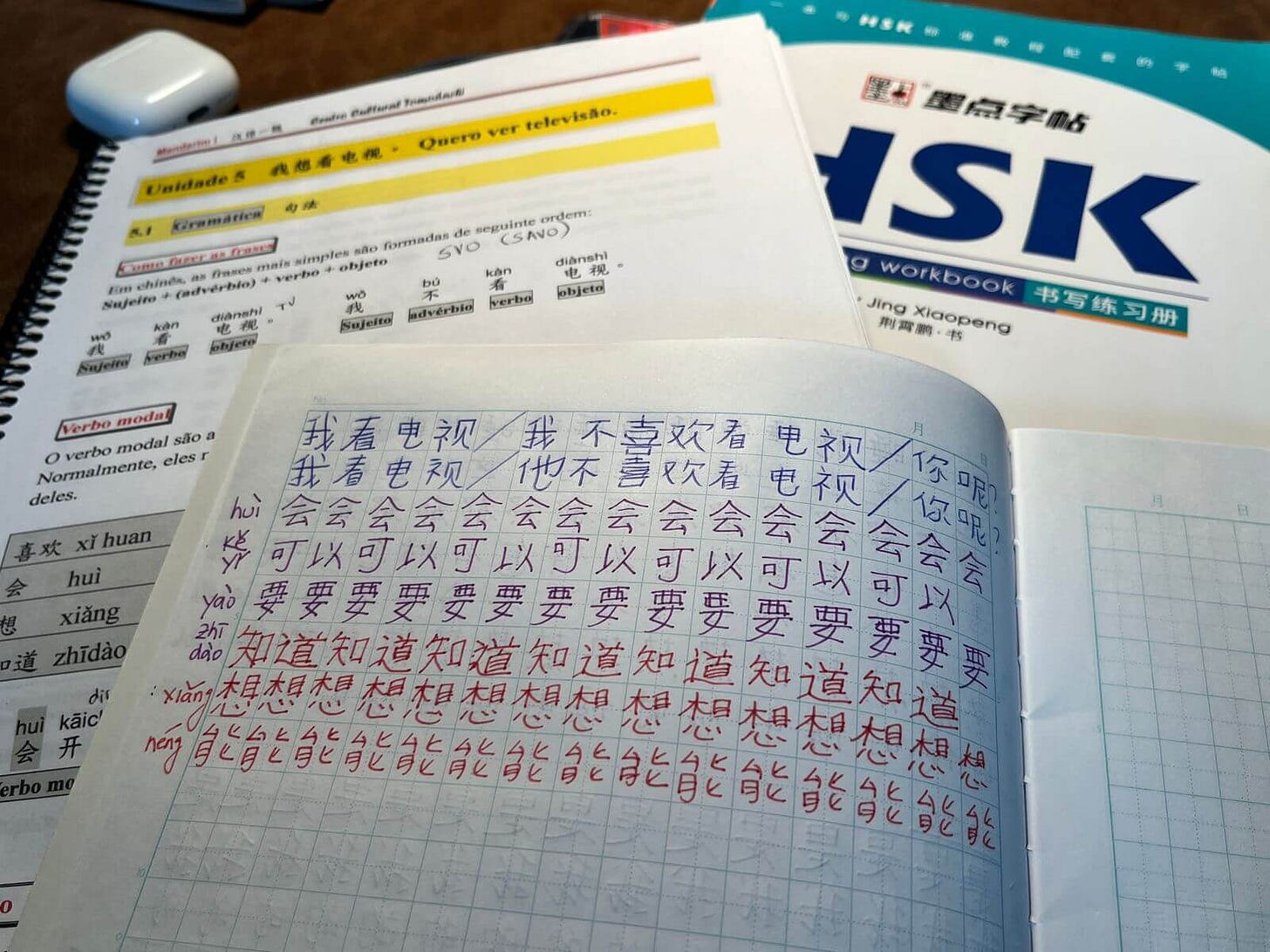

Aprender uma língua diferente depois dos 50 é muito difícil. Mas ensina humildade, paciência e resiliência; mais úteis nessa época da vida do que o próprio idioma. A professora fala e eu não entendo nada. Leio os exercícios do livro e, duas horas depois, já não consigo ler de volta. Não saio da fase book on the table, mas quem sabe daqui a uns dias já consiga articular pen on the sofa. Claro que é frustrante, ainda mais quando comprar 买 e vender 卖 são “mai”, só que com tons diferentes na hora de falar e um chapeuzinho a mais na hora de escrever.

Isso para não falar do caderno de caligrafia, que, quando vejo o resultado de repetidas tentativas escrevendo wo 我 (eu), parece a lição de casa de uma criança de três anos sendo alfabetizada no Tibete. Me pergunto como seria “alfabetizar” em mandarim se não usam o alfabeto. No lugar, eles têm algo que soa como “pobomofo”.

Vamos ver onde tudo isso vai dar. Acredito ser um bom plano para o futuro. Se um dia começar a esquecer o nome das pessoas e das coisas, quem sabe me lembre da frase duibuqi 对不起, “me desculpe”. Também vou torcer para que a próxima newsletter já saia de algum lugar do Oriente. O plano está montado, só falta passar na tal prova.

Zaijian, 再见 👋!

🇬🇧 I’ve devised a plan for the future. To try not to lose my mental agility, instead of doing crossword puzzles or Sudoku, I threw myself into Mandarin. I may never achieve enough fluency to watch a movie or even read a Chinese magazine. What matters is the journey. If it serves to occupy my neurons with characters, tones, and all the mystery of this ancient language, it will have been worth it.

🤷🏻♂️ paranoia #1 I read in a medical magazine that working at night or on alternating shifts increases the risk of dementia. I thought about the two years I spent as a Night Manager in London and the three years as an Emirates flight attendant in Dubai — and there’s no blueberry with creatine that can fill that hole. Mandarin now!

Speaking Mandarin is not a new plan. Six years ago, I was in this very same place. I even had an enrollment to study for two months at a language school in Beijing. I wanted to become semi-fluent so that later I could guide Chinese tourists in Paris. I went to São Paulo to apply for the visa at the Chinese Consulate at the end of March 2020. There were only a few of us. The Chinese people legalizing documents not to have to return to China looked at me with curiosity. Wuhan was already locked down.

I only gave up when my flight was canceled. The only option would have been to buy another ticket via Ethiopia and spend 14 days in quarantine in a bunker at Beijing airport before being allowed to move around the city with QR codes, masks, swabs up the nose (and even up the arse), and fear. Little did I know, in that March of 2020, that soon we would all be living something similar, washing our hands every hour and paranoid about everything.

The pandemic is gone. New problems came along. Some have already become part of the routine. The world turned upside down, and the desire to learn Mandarin remains very much alive. Because it is so difficult, almost impossible, it excites me even more, of course. I decided to treat it as an anti-dementia remedy so I won’t lose motivation. I promised myself that if I follow the online classes strictly and pass the first official test in February (very basic level), I’ll buy a ticket and head to China. I could copy the performance artist Marina Abramović and walk along the Great Wall. Or be a 21st-century Marco Polo.

🤷🏻♂️ paranoia #2 I am afraid to remake the 2020 plans now in 2026 and have the whole pandemonium happening again, pandemic and lockdowns comprised. ;-(

Learning a different language after 50 is very hard. But it teaches humility, patience, and resilience, more useful at this stage of life than the language itself. The teacher speaks and I don’t understand a thing. I read the exercises in the book and, two hours later, I can’t read them back. I’m stuck in the book-on-the-table phase, but who knows, maybe in a few days I’ll be able to articulate pen-on-the-sofa. Of course it’s frustrating, especially when buying 买 and selling 卖 are both “mai,” just with different tones when spoken and an extra little hat when written. Not to mention the calligraphy notebook: when I look at the result of my repeated attempts at writing wo 我 (“I”), it looks like the homework of a three-year-old child learning to write in Tibet.

Let’s see where all this leads. I believe it’s a good plan for the future. If one day I start forgetting the names of people and things, maybe I’ll at least remember the phrase duibuqi 对不起, “I’m sorry.” And I’ll also hope that the next newsletter will already come from somewhere in the East. The plan is set. All that’s left is to pass that exam in a few weeks.

Zaijian, 再见 👋!

Maravilhoso texto! Tanta leveza com coisas tão duras e difíceis na vida: demências…

Boa Vi. Um sonho a mais para realizar!

Sem paranoia kkkkk será uma aventura de um legítimo desbravador.

Sicesso!