Story: Malvinas. Não Maldivas!

🇬🇧🇦🇷 Malvinas. Not Maldives!

For English, please scroll down to 🇬🇧. Thanks!

Suíça, Suécia. Eslovênia, Eslováquia. Maldivas, Malvinas. Nomes tão parecidos, frequentemente confundidos, mas que, ao desembaralhar das letras, designam lugares completamente diferentes. No caso das Malvinas, tudo é tão intrincado que não me atrevo a puxar fios soltos. O terreno ainda é minado, mesmo após 40 anos do fim da guerra entre Reino Unido e Argentina.

Se eu tivesse que descrever o conflito em um tweet, seria algo como: ingleses abandonaram, argentinos invadiram, ingleses retomaram, argentinos não aceitaram. É claro que, para explicar os pormenores, talvez fosse necessário escrever um livro, uma tese de mestrado ou gravar um podcast. A história mudaria bastante dependendo de quem a conta — amigos argentinos ou ingleses. A melhor frase que li sobre o tema (e sobre todos os conflitos atuais) é um provérbio russo que diz mais ou menos assim: “É fácil transformar um peixe no aquário em sopa de peixe, mas muito difícil transformar uma sopa de peixe em um peixe no aquário.”

O que sempre atiçou minha curiosidade, até me convencer a pegar um avião e vir para cá, foram os cartazes ubíquos na Argentina que afirmam, em letras maiúsculas, que LAS MALVINAS SON ARGENTINAS. No ano passado, visitei o Museu das Malvinas em Buenos Aires, que me convenceu da enorme injustiça que foram os 70 dias de batalha nos anos 1980 (1982, para ser exato) e do poder imperialista dos britânicos. Apenas em 2020, quatro décadas após o armistício, as minas terrestres foram finalmente desativadas em todas as Falklands — ou melhor, Malvinas. Um exemplo de como as guerras nunca terminam quando parecem ter acabado.

Falklands e Malvinas são nomes diferentes para o mesmo lugar. Mais do que isso, representam projetos de domínio sobre este arquipélago perdido no meio do nada, refúgio de orcas, pinguins e golfinhos. Franceses, ingleses e espanhóis chegaram quase ao mesmo tempo, mas sem saber uns dos outros. A disputa pelo controle das ilhas dependia das alianças imperiais na Europa. Hoje, cerca de 3 mil pessoas vivem aqui, cercadas por 450 mil ovelhas. A bandeira é britânica, a moeda é a libra esterlina, e os supermercados são abastecidos com produtos da Inglaterra. God save the King.

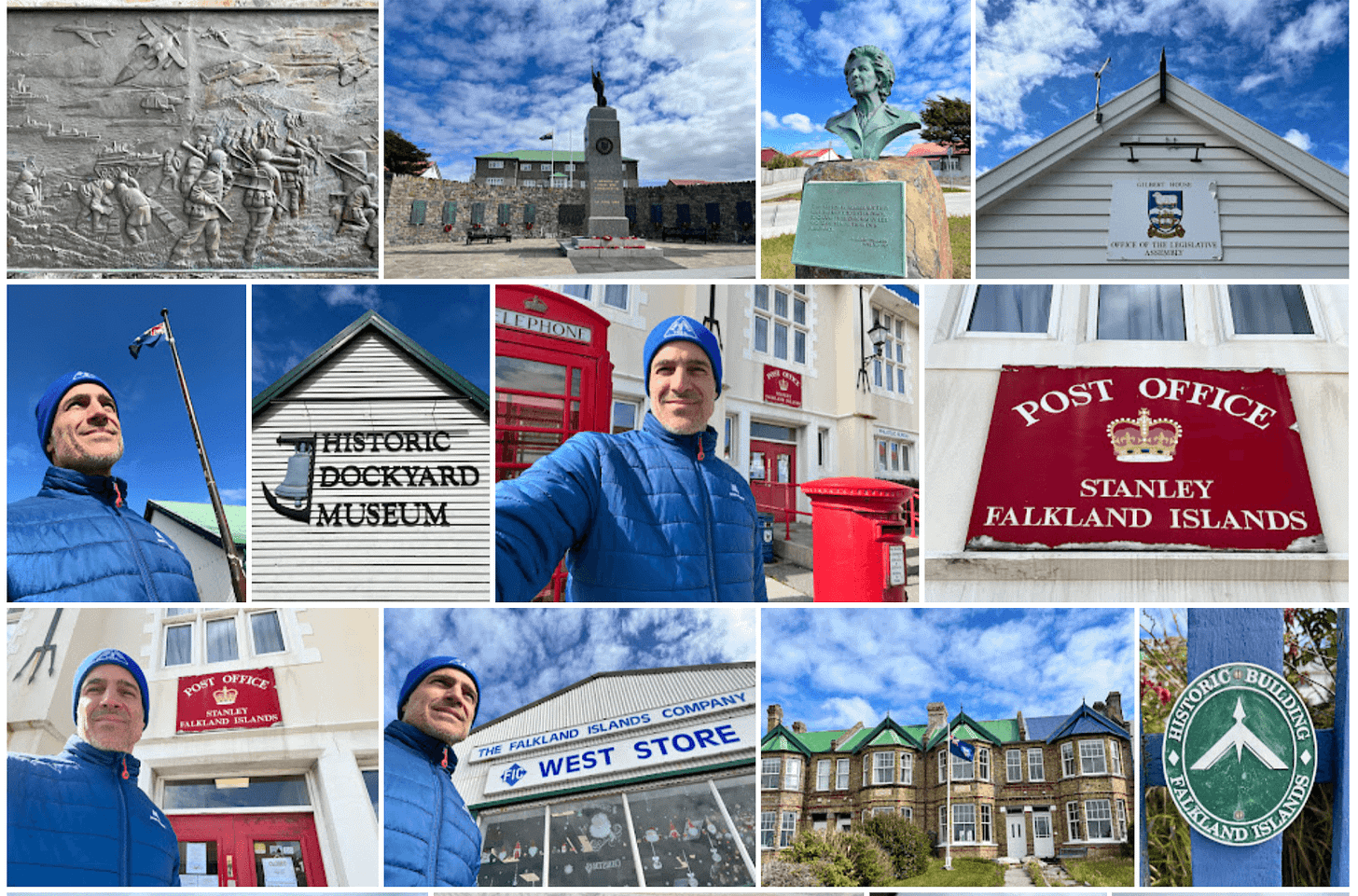

Port Stanley, a capital, parece cenário de uma série ambientada na Escócia. Casas geminadas, gramados bem cuidados, cabines telefônicas, carros no “lado errado” da estrada, e os intermináveis dias de verão. Fiz muitas caminhadas — a única atividade disponível (fora observar pássaros). Uma delas para ver os pinguins de Gipsy Cove, outra para observar os restos de uma cozinha militar argentina. Atravessei a baía de Stanley só para tirar uma foto com um ônibus double-decker londrino. Acabei no lixão da ilha, levado pelo vento ao longo de uma estrada bonita, até chegar à beira do mar, onde vi urubus e gaivotas disputando cascas de banana.

Sentado na beira do lixão, escondido do vento atrás de um contêiner, abri meu sanduíche de cheddar com picles de cebola, acompanhado de um pacotinho de batatinhas sabor vinagre. Os pássaros se agitaram, planando em círculos acima de mim. Eram muitos. Por que não se uniram para avançar? Por que as ovelhas não formam uma estratégia para tomar a ilha? São 150 para cada habitante humano. Se conseguissem uma aliança com as gaivotas, alistassem os urubus e recrutassem as quatro espécies de pinguins, pronto: las Malvinas son la revolución. George Orwell ficaria orgulhoso.

Do lixão, voltei para a pousada contra o vento, quase arrependido de ter ido tão longe. Pensei nos tais bichos que não se rebelam contra as forças opressoras; em Margaret Thatcher, que ordenou o ataque ao submarino argentino Belgrano; nos militares da Casa Rosada, que criaram uma guerra externa para mascarar os crimes internos; no aquecimento global; e na playlist da Mariah Carey que me aguardava na pousada. Felizmente, no dia seguinte, o avião da Latam viria me buscar.

🇬🇧 Burma and Borneo. Mali and Maui. Slovakia and Slovenia. Maldives and Malvinas. Names so similar, often confused, but once the letters are unscrambled, they refer to completely different places. In the case of the Malvinas, known in English as the Falklands, everything is so tangled that I don’t dare pull at any loose threads. The terrain remains metaphorically and literally mined, even 40 years after the war between the United Kingdom and Argentina.

If I had to summarize the conflict in a tweet, it would go something like this: the British left, the Argentinians invaded, the British reclaimed, the Argentinians didn’t accept it. Of course, to explain it in detail, I’d probably need to write a book, a master’s thesis, or record a podcast. The story would also vary greatly depending on whether it was told by Argentine or British narrators. The best phrase I’ve read about this topic—and about all modern conflicts—is a Russian proverb that says: “It’s easy to turn a fish in an aquarium into fish soup, but very hard to turn fish soup back into a fish in an aquarium.”

What always piqued my curiosity, eventually convincing me to hop on a plane and come here, were the ubiquitous posters in Argentina boldly declaring in capital letters that LAS MALVINAS SON ARGENTINAS. Last year, I visited the Malvinas Museum in Buenos Aires, which made a compelling case for the grave injustice of the 70-day conflict in the 1980s (1982, to be precise) and highlighted the imperialist power of the British. It wasn’t until 2020, four decades after the armistice, that all the landmines were finally deactivated across the Falklands—or rather, the Malvinas. Proof that wars rarely end when the soldiers go home.

Falklands and Malvinas are two names for the same place. More than just names, they symbolize competing claims over this remote archipelago, home to orcas, penguins, and dolphins. The French, British, and Spanish arrived almost simultaneously, unaware of one another. The fight for control over the islands often depended on shifting imperial alliances in Europe. Today, around 3,000 people live here, surrounded by 450,000 sheep. The flag is British, the currency is the pound sterling, and supermarkets are stocked with goods from England. God save the King.

Port Stanley, the capital, could easily serve as the set of a TV series set in Scotland. Terraced houses, well-kept lawns, red phone booths, cars driving on the “wrong” side of the road, and endless summer days define the scene. I went on many walks—the only real activity available. One took me to the penguins at Gipsy Cove; another to the remnants of an Argentine military kitchen. I crossed Stanley’s bay just to take a picture with a London double-decker bus. I even ended up at the island’s landfill, carried by the wind along a picturesque road, only to find myself by the shore, watching vultures and seagulls fight over banana peels.

Sitting by the landfill, sheltered from the wind behind a container, I opened my cheddar-and-onion-pickle sandwich, accompanied by a bag of salt-and-vinegar crisps. The birds grew restless, circling above me. There were so many of them. Why didn’t they band together and attack? Why don’t the sheep devise a plan to take over the island? They outnumber humans 150 to one. If they could form an alliance with the seagulls, recruit the vultures, and join forces with the four species of penguins, that would settle it. George Orwell would be proud.

From the landfill, I trudged back to the inn against the wind, almost regretting how far I had walked. I thought about those creatures that don’t rise up against their oppressors; about Margaret Thatcher, who ordered the attack on the Argentine submarine Belgrano; about the military leaders in the Casa Rosada, who ignited a war to cover up their crimes; about global warming; and about the Mariah Carey playlist waiting for me back at the inn. Luckily, the following day, the LATAM Airlines plane would come to take me home.